Home » Articles posted by Jesse Roach

Author Archives: Jesse Roach

Can Property Dualism Have Its Consciousness and Experience it Too? Part III

On a conceptual level, property dualism does not make much sense. Given a property dualist view, I’m often wondering how a nonreductive mental property could be instantiated in a physical substance. It seems odd how this could be coherent within the system. William G. Lycan expresses some of my same concerns. Lycan explains:

“Why or how on earth would a merely physical object, even one as complex as a brain, give rise to immaterial properties? We do not see how it could. If persons have immaterial mental properties, then most likely the persons themselves are or incorporate immaterial things. The idea would be that while there is nothing puzzling about an immaterial substance’s having immaterial properties, it is extremely strange to think that an otherwise purely physical object might have them.” (4)

This is what I find puzzling about property dualism. On a conceptual level it does seem that irreducible mental properties would have to be instantiated in a mental substance and not a physical one. Peter van Inwagen does not see how one can distinguish between properties. He says that properties are about things and do not ontologically differ. “[T]he properties that it is a cat and that it is an angel are things of exactly the same sort: they are both things that can be said about things… They differ not in their natures but in their content” (Inwagen 215). Now it is important to note that I am not making an argument against property dualism here. I am merely pointing out a problem I have with conceiving a non-physical property with a physical substance. The second thing that is to be noted is that Chalmers says that we “should take experience as fundamental” and a theory “requires the addition of something fundamental to our ontology, as everything in physical theory is compatible with the absence of consciousness” (Chalmers 1995; 14). Under Chalmers’s view why, is an irreducible mental property more fundamental than an immaterial mental substance? It seems that substance is more fundamental than property as property depends on substance to inhere to. Properties are contingent on the particulars. Both of these questions are not arguments. They could be areas of further reflection and discussion amongst property dualists and substance dualists. My skepticism about the above the coherence of property dualism could be boiled down to an incredulous stare. But, I do think there are legitimate arguments that establish substance dualism over property dualism.

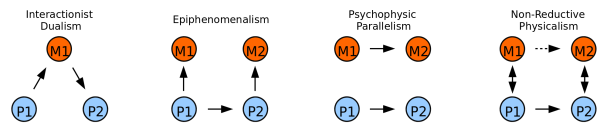

The first argument I will put forth is against epiphenomenalism. Chalmers does advocate a form of this view in his work. He finds it much more plausible than my view of interactionism (Chalmers 2003). Epiphenomenalism is the view that there is only a one-way interaction between the physical substance and the irreducible mental property. Interactionism argues that while there are two different substances both mental and physical, these both interact with one another and have a two-way causal relationship. Chalmers calls epiphenomenalism Type-E Dualism for short and interactionism Type-D Dualism (I will be using this same terminology) (Chalmers 2003; 29-36). On the onset, a Type-E view seems to be counter to our phenomenal experience. It seems that our P-consciousness is efficacious. Consider this thought experiment: suppose I have a vivid experience of the color red. Also, suppose I have no direct access to this experience – it is completely phenomenal. The experience is so wonderful in my subjective experience that it becomes my favorite color outside of my control. Now, suppose I want to buy a car. Could it be possible that my experience of red persuade me to choose a red car over a different color car? It is definitely possible and highly likely. People choose things on the basis of their subjective experiences all the time and many times these subjective experiences can be outside of their control. There does seem to be some sort of interaction from the mental states we have to the physical states in the world. What about the creation of art in general? Music, painting, poetry, cinematography, these are all subjective aspects of the human experience working in the physical world. It seems unlikely that these aesthetic preferences are anything but forms of P-consciousness. My phenomenal experience of hearing a great drummer such as Steve Gadd causes me to play the drums myself. Chalmers argues that the above objections to the Type-E view do not necessarily work. He relies on Hume’s view of causation in order to get around the above objections. He argues, in the same way Hume argues, that just because there is a seeming causal link between the mental and the physical does not in-fact show that there is (Chalmers 2003; 34). This objection is similar to a post hoc ergo proper hoc fallacy. This fallacy points out that just because event A comes before event B does not mean that event A caused event B. This is a valid criticism, but why think that event B causes event A (if we take event B to mean physical events and event A to mean mental events)? It seems like this Humean objection could also work in favor of forms of psychophysical parallelism, but it is unlikely that Chalmers would want to advocate that view. Parallelism is the view that there is no causal connection between the mental and the physical – they both run their causal course independently from one another. Typically, this view is advocated by substance dualists (Robinson). But, it seems that a property dualist such as Chalmers could also fall into this conundrum. In his view there are psychophysical laws that govern the mental (Chalmers 2003; 35). It seems possible that our experiences just coincidentally match up with physical events without any causal link between the two. I contend that if there is a two-way interaction between our experience and our physical states then a Type-D view is correct.

We have looked at strong reasons to reject epiphenomenalism, but now I wish to give a positive argument that establishes substance dualism. In his work Naming and Necessity, Saul Kripke gives us reasons to think that there can be necessarily true a posteriori truths. A necessary a posteriori truth would be an identity claim. The common example Kripke gives is that water is H20. This is a necessary truth that we discover empirically. The identity between water and its molecular structure is true in all possible worlds. It is impossible to conceive of water being something other than H20. The word water does not pick out any accidental properties it has but rather it picks out what it is, namely its molecular structure (Kripke 126-9). How can one use these Kripkean philosophical tools in order to understand the mind-body problem with more clarity? At the end of the book Kripke uses these concepts to explore identity theses of consciousness. He says that the type-type physicalist must prove a necessary identity between the stimulating of C-fibers and pain – that the mental and the physical are identical (144-46). This is why, as we saw, Chalmers’s zombie thought experiment works. If it is possible that the mental and the physical are not identical, then the mental and the physical are in fact not identical. Chalmers was relying on the modalities of distinguishing possibility and impossibility through our capacity of conceivability. But, as Kripke mentions, the converse of the zombie argument is also true. Kripke says the following about the identity of the mental and the physical:

“Here I have been emphasizing the possibility, or apparent possibility, of a physical state without the corresponding mental state. The reverse possibility, the mental state (pain) without the physical state (C-fiber stimulation), also presents problems for the identity theorists which cannot be resolved by appeal to the analogy of heat and molecular motion” (154).

Kripke seems to think that if you accept the zombie argument, you also have to accept that consciousness could exist without the physical instantiation. For the property dualist this would be a problem because consciousness is identical to a property or set of properties. But, properties have to be instantiated in substance. As Peter van Inwagen stated before, properties are about things. Thus, if consciousness can exist without being instantiated in a physical substance it must be instantiated in a mental substance. Swinburne follows Kripke’s same line of reasoning and gives a thought experiment that shows that a disembodied existence is possible. In order for a physical substance to be my body I must be able to move it and must be able to gain knowledge about the world through it. He imagines that he has powers that allow him to move a chair and learn about the world through the chair. He would not be tied down to merely acting through one physical substance. But Swinburne concedes that this does not show that consciousness can exist without a body (his consciousness still exists in the chair). He forms an argument that looks something like this:

- “It is logically possible that there be pure mental events which do not supervene on physical events.”

- “A person can have successive pure mental events”

- Conclusion: “Hence it is logically possible that I lose all contact with the physical world and yet still have thoughts and feelings”

Swinburne shows that this conclusion also entails that “since ‘I’ is an informative designator, it is not merely logically possible but also metaphysically possible that I could exist without my body; and what goes for me goes for any other human person” (163-4). A pure mental event is an experience of something that does not entail a physical reality. If it is false that mental events are the same as physical events, then it we can have pure mental events. We can “apparently hear the telephone” and “apparently see a desk.” They are experiences that a person has without any physical reality. The pure mental event is designated alone without any reference to a physical event (Swinburne 68-70). Swinburne’s whole argument stands or falls with the first premise just like the zombie argument. Chalmers would agree that premise (1) is true. The rest of the argument follows to the conclusion. Also, consider people who believe in God for a moment. If theism is possibly true then consciousness can exist independently of a physical body. Theism views God as an immaterial entity that exists without a body. God seems to be conceivable to many people and is not an incoherent concept. Lycan tells us to “remember that the conceptual possibility of disembodied existence is granted by nearly everyone, the only exceptions being Analytical Behaviorists and (if any) Analytic Eliminativists” (6). I have shown that given property dualism, substance dualism can be established.

Chalmers is motivated to accept property dualism over substance dualism for two key ontological constraints. The first is parsimony. This constraint takes simplicity to be a good principle when choosing a metaphysical framework (Chalmers 1995; 16-7). William of Ockham has said that we “shouldn’t multiply entities beyond necessity.” There are many interpretive challenges with this principle (Baker). For example, what does necessity mean? Property dualism might be simpler than substance dualism – it does only posit one substance as opposed to two – but, as I have shown, it does not explain all the data of consciousness. I contend that substance dualism does all the necessary ontological work that property dualism cannot do. Parsimony gives us a cleaner ontology without pluralistic messiness but it does not necessarily guide us to the truth. The second principle that constrains Chalmers’s ontological commitments is a naturalistic presupposition. He rejects substance dualism and interactionism because the universe is causally closed (Chalmers 2003; 30). But this seems to be nothing more than an unwarranted and asserted constraint that is based in a naturalistic presupposition. I do not think that either of these constraints is viable in producing a true ontology.

Given the arguments for property dualism, physicalism is in a problematic philosophical place. I have contended that, given the arguments for substance dualism property dualism is in a similar problematic place as physicalism. The problem of consciousness is still a live philosophical debate and it is only with clear principles that one can get to the truth.

Works Cited

Baker, Alan. “Simplicity.” Stanford University. Stanford University, 29 Oct. 2004. Web. 08 June 2015. <http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/simplicity/>.

Chalmers, David J. “Consciousness and Its Place in Nature.” Papers on Consciousness. N.p., 2003. Web. Apr.-May 2015. <http://consc.net/papers/nature.pdf>.

Chalmers, David J. “Facing Up to the Hard Problem of Consciousness.” Papers on Consciousness. N.p., 1995. Web. Apr.-May 2015. <http://consc.net/papers/facing.pdf>.

Inwagen, Peter Van. “A Materialist Ontology of the Human Person.” Persons: Human and Divine. Oxford: Clarendon, 2007. 199-215. Print.

Kripke, Saul A. “Lecture III.” Naming and Necessity. Oxford: Blackwell, 1980. 106-55. Print.

Lycan, William G. “Is Property Dualism Better Off Than Substance Dualism?” (2012): n. pag. 2012. Web. 5 June 2015. <http://www.unc.edu/~ujanel/Is%20Property%20Dualism%20Better%20Off%20than%20Substance%20Dualism_January%202012.pdf>.

Robinson, Howard. “Dualism.” Stanford University. Stanford University, 19 Aug. 2003. Web. 07 June 2015. <http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/dualism/#Par>.

Swinburne, Richard. Mind, Brain, and Free Will. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2013. Print.

Can Property Dualism Have Its Consciousness and Experience it Too? Part II

Philosopher David Chalmers argues that any version of physicalism cannot provide an adequate explanation of consciousness and how we have both mental states and physical states. In his essay Facing Up to the Problem of Consciousness, he distinguishes two different problems of consciousness as the easy problems and the hard problems (Chalmers 1995; 1-2). The easy problems are in explaining phenomena such as reportability of mental states, the focus of attention, the deliberate control of behavior and so on. He believes that this can all be explained scientifically and that the explanations for these can be reduced. We can explain the functionality of these phenomena (Chalmers 1995; 4). The hard problem on the other hand is a problem of how we come to have experience. The problems of consciousness that are considered hard problems cannot be adequately explained by scientific methods. For Chalmers, experience of the world is synonymous with qualia. He thinks that the hard problem is in how we explain how we have an experience of color or an experience of anything at all. Chalmers asks the question, “why should physical processing give rise to a rich inner life at all? It seems objectively unreasonable that it should, and yet it does” (Chalmers 1995; 3). The basic functions of the brain can be explained in reductive terms but the experiences cannot. Chalmers says there is an explanatory gap between the physical functions and conscious experience and we need an explanatory bridge in order to overcome this gap (Chalmers 1995; 6).

Chalmers proposes five strategies researchers in neuroscience and philosophers can take in approaching this explanation of consciousness. The first is to explain something other than the hard problems of consciousness. This strategy doesn’t really do much to forward our knowledge about how to come up with a bridge. It stays on the “easy” side of the gap (Chalmers 1995; 9). The second way is be an eliminativist about consciousness and deny its existence. Chalmers thinks that this is quite absurd and seems to be assuming a type of verification principle. He says that “a theory that denies the phenomenon ‘solves’ the problem by ducking the question” (Chalmers 1995; 9). A third option is for researchers to explain consciousness in the full sense, yet Chalmers thinks theories that which go for this option are nearly magical. This strategy doesn’t explain how consciousness emerges (Chalmers 1995; 9). A fourth approach seeks to explain the structure of experience. By explaining the visual structures in the brain one can explain how that relates to color. This strategy would still amount to staying on the “easy” side of the gap as opposed to actually building a bridge between the hard and easy problems (Chalmers 1995; 10). The last method is to “isolate the substrate of experience.” This method tries to “pick out” which process accounts for experience. This is still an inadequate strategy because we need to know why and how the process gives us consciousness. Chalmers parts ways philosophically with these five strategies because he thinks we need an “extra ingredient” to give us an adequate explanatory bridge (Chalmers 1995; 10). Given that all of the reductive explanations fail, we need a nonreductive explanation. He argues that “a nonreductive theory of experience will add new principles to the furniture of the basic laws of nature.” This theory adds properties as being fundamental (Chalmers 1995; 14). He admits that his position is a form of property dualism – what he calls naturalistic dualism.

Before we look at the arguments that Chalmers advocates for property dualism, we need to first make a few distinctions between different types of consciousness. When people talk about consciousness, invariably it seems like they’re talking about one thing. All the definitions of consciousness appear to be lumped together into one concept. Philosopher Ned Block thinks this is a misinformed notion and that there are different types of consciousness. Having a conceptual framework as to what consciousness is will help us tackle the problems of consciousness with more clarity and precision. Block’s first distinction of consciousness is phenomenal consciousness or what he likes to call P-consciousness. P-consciousness is the state of “what-is-it-like-ness” (Block 206). This type of consciousness is experiential. It is just one type of consciousness we have. This type of consciousness includes “properties of sensations, feelings and perceptions… thoughts, wants and emotions.” These properties are distinct from functional and cognitive properties of the brain (Block 206-7). Another type of consciousness is access consciousness or A-consciousness. “A representation is A-conscious if it is broadcast for free use in reasoning and for direct “rational” control of action (including reporting)” (Block 208). This A-consciousness is a direct awareness and form of reasoning in the mind, while P-consciousness is just states of experience or feelings.

This distinction can help us understand the easy and hard problems of consciousness with more clarity. The easy problems of consciousness are related to Block’s A-consciousness. They are forms of consciousness that we use to focus, control our behavior, and so on. This type of consciousness is still a form of consciousness. It isn’t any more or less important. The hard problem of consciousness would be problems of P-consciousness. Finding an explanatory bridge to the question “what is it like to be such and such” is a much harder question then seeing how the brain functions with forms of A-consciousness. It is with these conceptions in mind that we now will look at three arguments that Chalmers puts forth that will motivate people to a form of property dualism. It is careful to note that these arguments have type-type identity, and functionalism in its sights. They are arguments that seek to show the falsity of physicalist identity theories or notions of functional properties supervening on physical and mental states.

In his essay Consciousness and Its Place in Nature, David Chalmers considers two important arguments establishing that physicalism is false because it cannot explain the full scope of consciousness. The first argument is a conceivability argument. Chalmers asks us to imagine that there be a being that is physically identical to us. This being has all the same brain properties and brain states. If you scanned their brain everything would check out as being identical to our brain structure. These entities would even have access consciousness and would be able to be awake, report the contents of his internal states and so on (Chalmers 1996; 95). But, as it turns out, they lack any phenomenal conscious state. This entity is called a philosophical zombie. Unlike the zombies in movies and television, these zombies appear to be exactly the same as humans – in both behavior and on a neuronal level. They have absolutely no inner feel and do not have any experience of the world. If you were to ask them if they are conscious, they would tell you that they are. Chalmers states the argument as follows:

- It is conceivable that there be zombies.

- If it is conceivable that there be zombies, it is metaphysically possible that there be zombies.

- If it is metaphysically possible that there be zombies, then consciousness is non-physical.

- Conclusion: Consciousness is non-physical. (Chalmers 2003; 6)

These zombies are the same as us in regards to A-consciousness but are not the same as us in regards to P-consciousness, to reiterate Block’s distinctions. Chalmers is concerned with phenomenal zombies (Chalmers 1996; 95). Now it has to be said that much of this argument either succeeds or fails with premise (1). Conceivability is used to generate possibility. If I can conceive of X, then X must at least be possible. It is important to note that this phenomenal zombie might not in-fact be able to exist in the actual world. There might be physical limitations to this existing in our world. But, it does seem that these zombies can exist in at least some possible world, merely because they are conceivable. There doesn’t seem to be any contradiction in the idea of phenomenal zombies. It is a coherent idea. Chalmers argues that some burden of proof lies with the person who wants to argue that zombies are logically impossible (Chalmers 1996; 96). He gives a different example of the idea of a mile-high unicycle which he thinks is also a possibility. He says that if “a mile-high unicycle is logically impossible, she must give us some idea of where the contradiction lies, whether explicit or implicit” (Chalmers 1996; 96). The same burden falls on the person who wants to deny zombies. This argument shows that consciousness does not metaphysically or logically supervene on the physical and that consciousness must be non-physical (Chalmers 1996; 97). The phenomenal properties can differ without a difference in the physical properties and thus the phenomenal properties do not metaphysically or logically supervene on the physical properties.

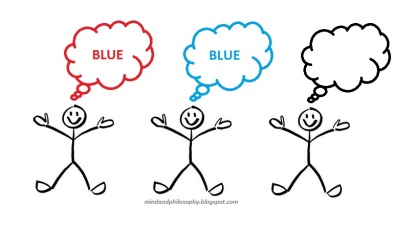

Maybe the zombie argument is not convincing for a functionalist or a type-type theorist. Consider another argument of the inverted spectrum. The argument relies on some of the same intuitions as the zombie argument but the intuitions are much more localized. The zombie argument considers the whole physical identity of an entity with respects to phenomenal consciousness, while the inverted spectrum argument considers the function of the visual color spectrum and how it relates to experience. It seems possible that you can have two people who are identical to each other yet one of them has an inverted color experience. Person X has properly functioning vision (his brain is ordered in the proper way) and picks out apples, firetrucks, and strawberries as being red objects. This person experiences red. Person Y, on the other hand, picks out these same objects as being red, yet has the experience of green. Person Y has inverted vision. How can this be possible? It seems possible that we can change the brain structures in such a way to have this inversion. This argument is successful at showing that the function of person X can be completely identical to the function of person Y and yet both lead to two totally different experiences. If the functions are the same, why are the generated experiences fundamentally different? “Somebody might conceivably hold that inverted spectra but not zombies are logically possible. If this were the case, then the existence of consciousness could be reductively explained, but the specific character of particular conscious experiences could not be” (Chalmers 1996; 99-101).

Let us consider a final argument known as the Mary Argument. This argument involves a thought experiment. Imagine a neuroscientist named Mary. She is the leading expert in her field when it comes to her knowledge about how color operates, how our eyes pick up the light from color, and how our brain functions during that process. She knows all the physical facts about vision and the brain. But, as it turns out she has been raised in a black-and-white room. She has never experienced color. We can imagine her opening the door and leaving the black-and-white world and going into the world of color experience. Since she has never had any experience of color before, her entrance into the colored world will add more information to her knowledge about vision and the brain. Prior to opening that door, she knew all the physical facts about color but, after opening the door she learned something new – the way it feels to subjectively experience color (Chalmers 2003; 7). As a helpful analogy, consider the movie The Wizard of Oz. Dorothy grows up and lives in a black and white world her whole life. Yet, when she enters the world of Oz for the first time she learns something new about subjective experience of color. The Mary argument is similar to this, but it is different because Mary has full knowledge of all the physical color facts. This argument can be put as such:

- Mary knows all the physical facts.

- Mary does not know all the facts

- Conclusion: The physical facts do not exhaust all the facts. (Chalmers 2003; 7)

This argument shows that we cannot gain all the facts of the world merely by having a list of all the physical facts. Indeed, Richard Swinburne says that a full history of the world must include public facts and facts in which we have private access to (in this case, Mary’s subjective experience of color) (Swinburne 67-70).

We have established that these arguments minimally lead to a form of property dualism and that these arguments give us an explanatory bridge for the hard problem of consciousness. I do not believe that one can consistently hold a view that resembles Chalmers’s view. Since I still maintain that the three arguments are successful, I think that one must embrace a form of substance dualism. I have briefly explained this view earlier, but let me reiterate it again. Substance dualism is the view that there are two distinct substances (mental and physical substances) with respective properties and that these two substances interact with one another. Another entailment of this view is that the self is essentially a pure mental substance and not a physical substance. I am now going to argue that property dualism motivates towards substance dualism and that property dualism has more problems than substance dualism. I will argue that property dualism has some conceptual challenges. Moreover, I will give a negative and a positive argument against a form of property dualism, specifically, Chalmers’s view. Lastly, I will briefly examine some metaphysical constraints that may or may not be beneficial in determining one’s metaphysical framework.

Works Cited

Block, Ned. “Concepts of Consciousness.” Philosophy of Mind: Classical and Contemporary Readings. New York: Oxford UP, 2002. 206-18. Print.

Chalmers, David J. The Conscious Mind: In Search of a Fundamental Theory. New York: Oxford UP, 1996. Print.

Chalmers, David J. “Consciousness and Its Place in Nature.” Papers on Consciousness. N.p., 2003. Web. Apr.-May 2015. <http://consc.net/papers/nature.pdf>.

Chalmers, David J. “Facing Up to the Hard Problem of Consciousness.” Papers on Consciousness. N.p., 1995. Web. Apr.-May 2015. <http://consc.net/papers/facing.pdf>.

Swinburne, Richard. Mind, Brain, and Free Will. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2013. Print.

Can Property Dualism Have Its Consciousness and Experience it Too? Part I

Consciousness is puzzling. It is something we are immediately aware of, yet at the same time it is equally mysterious. We experience the world but it seems hard to grasp how we can explain our experience adequately to another person. Why do we have an experience of the world and why is this experience subjective? A metaphysical framework will be the main tool in how one approaches and explains the problem of consciousness. There are two broad views that one can adopt in addressing this question. The first is a physicalist view of consciousness. Physicalism is the thesis that human beings are only a physical thing with physical properties and that consciousness can be explained through purely physical processes in the brain. Historically, this view has also been called materialism but over the past hundred years the term physicalism has become more popular, though both can be used interchangeably. Dualism, which is the second view, posits two different things in the ontological framework. There are two positions of dualism in philosophy of mind – property dualism and substance dualism. Property dualism is the view that human beings are a physical substance which has physical properties and irreducible mental properties and that consciousness can be explained in terms of both these physical properties and mental properties. Property dualism treats these properties as being fundamentally different from one another. Substance dualism on the other hand, is the view that humans have both a physical substance – their body – and an immaterial substance – their soul. Under this view these two substances are distinct from one another and interact with one another in a two-way relation. This view also holds that human beings are essentially their soul and that when the body dies the soul can still continue to exist. Advocates of both forms of dualism argue that the physicalist picture is not adequate in explaining what consciousness is and how we have it. A handful of philosophers in the philosophy of mind have been adopting a property dualist view because of skepticism about physicalism’s explanatory power. In this paper I will show that arguments that lead to property dualism are correct as a critique of physicalism’s ability to give an explanatory bridge of consciousness, but I will argue that property dualism is an untenable middle ground position and pushes one towards a substance dualism.

We must first understand what physicalism is in order to understand the context of the critiques of it. I have stated that physicalism is the thesis that human beings are only a physical thing with physical properties and that consciousness can be explained through purely physical processes in the brain. There are different ways as to how the physicalist can address this explanation. Eliminativist theories do not regard consciousness as a thing to be explained because they deny its existence outright. More modest eliminativist views deny certain features of consciousness such as qualia (Gulick). “Qualia is plural for quale, which means a specific experiential quality – for example, what it is like to experience redness or blueness” (Moreland 257). Eliminativism does not regard consciousness as a viable conceptual scheme (Gulick). Behaviorism is the view that mental states can be merely characterized as behavior states. I can know the mental state of a person by observing their behavior. When someone pricks me with a pin, you can determine my pain by my reaction to the pin. Thus, behavior states can be used to explain conscious states (Moreland 250). A type-type identity theory treats physical states as being the same as mental states. This view takes a phenomenal experience such as seeing red as identical to a physical brain state. If mental states are identical to physical brain states then no explanation is needed as to how mental states emerge from physical states (Gulick). A functionalist physicalist theory sees consciousness as a function or role of the brain. This view relies on realizability in order to explain how mental states and physical states relate (Gulick). A common analogy to explain this view is the difference between computer hardware and software. Philosopher J.P. Moreland says that “this is similar to requiring that only some sort of physical hardware can be the realizer of functional roles specified in computer software.” Functionalism does not regard mental states as having intrinsic features but only extrinsic features by the roles they play within the organism (Moreland 249).

It is important to discuss the notion of supervenience in philosophy of mind and more importantly how it relates to functionalism. In his book Mind, Brain, and Free Will, Richard Swinburne says that “functionalists claim that science has shown that the only events in humans caused by input to sense-organs and causing behavioural output are brain events. Hence many brain events are events with functional properties which supervene on brain properties” (95) Terence Horgan defines supervenience as:

a determination relation between properties or characteristics of objects. The basic idea is this: properties of type A are supervenient on properties of type B if and only if two objects cannot differ with respect to their A-properties without also differing in their B-properties (150).

For example, “a utilitarian may urge that moral properties supervene on properties measuring human happiness.” So, if there is a change in the properties measuring human happiness, there is a change in the moral properties according to the utilitarian (Swinburne 22). It is important to have this definition of supervenience when discussing concepts in the philosophy of mind. Given these brief sketches of some physicalist pictures of consciousness, I will now show how other philosophers have responded to these views. Type-type and functionalist views are the two most popular of the four. Behaviorism is rejected by most physicalists, and eliminativism does not even enter the discussion on consciousness. Consequently, this paper will focus on the former two views.

Works Cited

Gulick, Robert Van. “Physicalist Theories.” Stanford University. Stanford University, 18 June 2004. Web. 27 May 2015. <http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/consciousness/#PhyThe>.

Horgan, Terence. “From Supervenience to Superdupervenience.” Philosophy of Mind: Classical and Contemporary Readings. New York: Oxford UP, 2002. 150-62. Print.

Moreland, James Porter, and William Lane. Craig. “Dualism and Alternatives to Dualism.” Philosophical Foundations for a Christian Worldview. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 2003. 228-66. Print.

Swinburne, Richard. Mind, Brain, and Free Will. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2013. Print.

Proper Function and Religious Pluralism

Philosopher Alvin Plantinga has put forth notable ideas in both epistemology and philosophy of religion. Plantinga’s epistemology is foundationalist but it is novel by the fact that it relies on what he calls proper functionalism. His primary work in epistemology can be seen in his books Warrant: The Current Debate (WCD), and Warrant and Proper Function (WPF). However, in his book Warranted Christian Belief (WCB), he examines the intersection between philosophy of religion and epistemology. In this third book, Plantinga argues that a person can have belief in God without argument or evidence and still have rational grounds in their belief. Many objections are raised against Plantinga’s proper functionalism, the most notable being the issue of religious diversity. In this paper I will be explaining the de facto and de jure objections to religious belief, Plantinga’s arguments against classic epistemic positions, the role of warrant and proper function, and what Plantinga calls the Aquinas-Calvin model. All of this will provide a backdrop to the issue of disagreement and its relation to religion. Using the tools Plantinga offers, I will be arguing against religious pluralism and showing why this view does not affect Christian exclusivism.

Philosopher Alvin Plantinga has put forth notable ideas in both epistemology and philosophy of religion. Plantinga’s epistemology is foundationalist but it is novel by the fact that it relies on what he calls proper functionalism. His primary work in epistemology can be seen in his books Warrant: The Current Debate (WCD), and Warrant and Proper Function (WPF). However, in his book Warranted Christian Belief (WCB), he examines the intersection between philosophy of religion and epistemology. In this third book, Plantinga argues that a person can have belief in God without argument or evidence and still have rational grounds in their belief. Many objections are raised against Plantinga’s proper functionalism, the most notable being the issue of religious diversity. In this paper I will be explaining the de facto and de jure objections to religious belief, Plantinga’s arguments against classic epistemic positions, the role of warrant and proper function, and what Plantinga calls the Aquinas-Calvin model. All of this will provide a backdrop to the issue of disagreement and its relation to religion. Using the tools Plantinga offers, I will be arguing against religious pluralism and showing why this view does not affect Christian exclusivism.

There are two types of criticisms that are aimed at religious belief. The first is to show that God does in fact not exist. This is the de facto objection to belief in God. Typically atheists or agnostics have appealed to arguments such as the problem of evil to show a logical incompatibility between God’s attributes and the existence of evil. By contrast, the second type of criticism is to show that belief in God is irrational. This is the de jure objection. This objection does not seek to show that God does not exist – maybe it’s impossible to show that God does not exist – nevertheless is seeks to show that belief in God is irrational and is not up to intellectual standards (WCB 15). Plantinga’s goal is to defeat the de jure objection by showing that one can believe in God without argument or evidence. But what would a de jure objection look like? Plantinga considers possible de jure objections from classical views in epistemology and possible objections from Freud and Marx.

In chapter 3 of Warranted Christian Belief Plantinga discusses three classical views within epistemology that have dominated much of the history of philosophy and have caused a lot of confusion as to what counts as knowledge and what counts as justification. These views are classical foundationalism, deontologism, and evidentialism. These all rely on similar principles and have similar assumptions in common. Could a proper de jure objection be found amongst these? Is belief in God justified? Plantinga first considers classical evidentialism. John Locke is the main proponent of this view. Under this view, belief in God is justified if and only if there are good arguments, reasons, or evidence in favor of His existence (WCB 73-4). This view is connected to both classical foundationalism and deontologism. Foundationalism sees knowledge as a structure similar to a house. There are beliefs we hold which are dependent on other propositions within our noetic structure. Consider much of our knowledge about mathematical truths. Beliefs about geometry or trigonometry depend on beliefs about basic arithmetic. Beliefs such as these would not be fundamental or foundational to our belief structure. These beliefs would be perhaps the walls of the belief structure but definitely not the foundation. They require other beliefs or propositions in order to be held. Fundamental beliefs are known as basic beliefs. You can think of these beliefs as being at the foundation of the structure not relying on propositions or arguments for it to be held. One could hold a belief about a sense perception in a basic way. When I look outside I believe it to be dark. But, I do not believe this on the basis of argument. I take my sense perception as a starting point for my belief structure. Plantinga says that “if A is nonbasic for me, then I believe it on the basis of some other proposition B, which I believe on the basis of some other proposition C, and so on down to a foundational proposition or propositions.” This is a broad explanation of what foundationalism is (WCB 73-5). What distinguishes classical foundationalism? Classical foundationalism will regard properly basic beliefs as requiring certainty. Descartes thought these beliefs had to be self-evident or incorrigible. Locke admitted that properly basic beliefs had to be evident to the senses (WCB 75). Under this view, belief is God is rational and justified if and only if it is properly basic (as defined by Descartes and Locke) or if it has proper evidence to support it. This is classical deontologism. We are not meeting our epistemic duties if our beliefs do not meet the standard of classical foundationalism. A de jure question based off this epistemology would show that belief in God is not properly basic (it’s not self-evident or incorrigible that God exists) and it would also show that there can never be good evidence for belief in God (WCB 77-9). All three of these views are dubbed the “classical package” or CP for short. Plantinga argues that this standard of justification is self-defeating. The CP cannot be believed by its own standards of justification. The classical package itself would not be self-evident, incorrigible, or evident to the senses. Thus, it cannot be properly basic. Can an argument be given for the belief in the classical package? Plantinga doesn’t see any arguments or evidence given to justifiably believe in CP (WCB 84-6). A second problem with this view is that under it most of our beliefs would not fit its standard. We can see radical skepticism through the history of modern philosophy up until the Enlightenment. It seems that most of our beliefs would not be justified because they are neither properly basic nor are they believed with proper evidence or argument. This gives us reasons to abandon this view because of its incoherence (WCB 87). Hence, a proper de jure question cannot be found here.

Plantinga considers complaints from Sigmund Freud and Karl Marx. He thinks that these complaints from Freud and Marx can generate a proper de jure question. Freud contends that religious belief comes from wish fulfillment. Belief in God is just an illusion that fulfills our desires. According to Freud, this illusion can be disbelieved (WCB 119-20). Karl Marx on the other hand thinks that theistic belief is the result of a cognitive defect resulting from the capitalistic structure. Theism is an “opiate of the masses” and a false ideology. Marx considers religious people mentally defective and insane (WCB 120-1). Both Freud and Marx are giving naturalistic explanations of how theistic belief rises. They are not critiquing the truth of theism (WCB 124). The core of the complaint is that theistic belief is the result of malfunctioning cognitive faculties not aimed at truth. It is either from wish fulfillment or capitalistic brainwashing. Plantinga considers this a viable de jure question. They are complaining that theism lacks warrant (WCB 128-30).

Warrant is a key idea in Plantinga’s epistemology. This word is similar to justification. If a belief is warranted then that belief is held in the proper way. It is acceptable to hold a belief if it is warranted (WCD 3). There are two ways to understand warrant. The first way is internalism. Warrant is dependent on internal states in a person’s epistemic functions. It relies on properties that are internal to the individual. There is a type of special access that is required for warrant. Warrant can be determined by reflection and consideration (WCD 5). Externalism would reject that warrant is dependent on this internal special access. Warrant depends on things outside of the individual’s control. For a belief to be warranted, it would have to arrive by a properly functioning mechanism (WCD 6). Plantinga takes an externalist position on warrant to address how belief in God is rationally acceptable.

Before we can see how Plantinga models Christian belief, we need to understand what proper function means in the context of warrant. Minimally, a belief has warrant if the cognitive faculties are working properly. There are other considerations that also fit into the definition of a properly functioning cognitive faculty. They are dysfunction, design, function, normality, damage, and purpose (WPF 4). The externalist sees our epistemic system in a similar way to how we see other bodily organs. Cataracts, for example, cause fogginess in the lenses of the eye and thus the eye does not function properly. Illegal drugs damage the brain and cause it to malfunction and sometimes create false beliefs which result in hallucinations (WPF 5). Warrant with respect to proper function also requires a proper environment. A cognitive faculty might be functioning properly yet the environment could cause false beliefs. A properly functioning mechanism must be in the correct environment that fits its design (WPF 7). There are two more characteristics to proper function: design plan and reliability of producing true beliefs. What Plantinga means by design is not necessarily a teleological definition. If naturalism is true, then the design plan of our faculties would be for the purpose of survival and natural selection. The same holds true for other organs of the body such as the heart. The heart’s purpose is to pump blood and keep the organism alive. A good design plan is one that is aimed at truth. The faculties might not deliver true beliefs every time, but, the probability that it will is high (WPF 13-20). It is with this externalist explanation of warrant with respect to proper function that we can understand the epistemic model that Plantinga puts forth to overcome Freud and Marx’s de jure question.

It is helpful to note that Plantinga’s overall aim in Warranted Christian Belief is to give Christians a defense of their faith. Chapter 6 is devoted to laying out the Aquinas/Calvin model of religious belief. This model is meant to address the Freud and Marx complaint. This model is based in the thought of Thomas Aquinas and John Calvin. Both of these thinkers thought that people have an innate knowledge of God of some sort. Our cognitive mechanism has this natural divine sense. Calvin calls this the sensus divinitatis. Beliefs about God are triggered in us in the appropriate circumstances we find ourselves in (WCB 142-4). We can find ourselves looking at the earth and all its beauty, the fine-tuning of the universe and its complexities, or maybe looking at cloud structures. Belief in God can be triggered by this wonder of the design and complexity of the universe (WCB 145). Theologians call this general revelation. General revelation is God revealing Himself through nature. In the letter to the Romans, Saint Paul says that God’s invisible attributes are seen through nature and it is there so we are without excuse (WCB 143). The fingerprints of God are on the created order. General revelation is contrasted with special revelation. Special revelation is God’s revelation through the Biblical canon and testimony of His apostles in the Gospels. Knowledge about God through the sensus divinitatis is basic and not arrived by argument or evidence. Plantinga, while quoting Psalm 19, says that “the heavens declare the glory of God and the skies proclaim the work of his hands: but not by way of serving as premises for an argument” (WCB 146). Beliefs produced by the sensus divinitatis are similar to beliefs about sense perception, memory, and a priori belief. We hold beliefs about sense perception in a basic way. I take sense perception to be generally reliable (but not with the standards of absolute certainty as Locke did) and I do not have arguments or evidence for my sense perceptions. I arrive at beliefs about memory in the same basic way and the same goes for a priori beliefs. These things, sense perception, memory, and a priori beliefs, are starting points for the foundation of our noetic structure (WCB 147). Plantinga contends that under this model belief in God is properly basic with respect to justification. Here he means subjective justification. The believer is not violating her epistemic rights by holding this belief in God in a basic way. The believer might consider Freud and Marx and maybe other atheist complaints against religion. Furthermore, they might have taken a course in philosophy of religion and studied objections against God’s existence yet still be convinced that God is real. Likewise, this knowledge of God is properly basic with respect to warrant. The cognitive faculties are functioning properly in the right environment according to their design and are aimed at truth. “The purpose of the sensus divinitatis is to enable us to have true beliefs about God; when it functions properly, it ordinarily does produce true beliefs about God. These beliefs therefore meet the conditions for warrant” (WCB 149).

From this model Plantinga draws three entailments. The first is that if God does not exist then theists are probably not warranted in their belief. If God does not exist then a sensus divinitatis does not exist. It would be hard to see how theism could be warranted if God did in fact not exist. The second entailment is that if God does exist then theistic belief is warranted. God would have given us the sensus divinitatis so we could know Him and worship Him. Finally, Plantinga shows that a proper de jure question is not independent of a de facto question. In order to criticize the rationality of theism, one would need to show theism to be false. The A/C model stands or falls ultimately on the de facto question (WCB 155-60).

A common objection to Plantinga’s Reformed epistemology is the problem of religious pluralism. How can someone such as Plantinga hold an exclusivist view in Christianity? John Hick argues for religious pluralism. He does not consider all religions to be true, but rather than all religions are false. Hick argues that there is an ultimate reality to which he calls The Real and that all religions are grasping for The Real but get it wrong. The Jew, Muslim, and Christian are all trying to describe The Real based on their own interpretation (Stairs 253-4). It seems pompous to claim to one religion when there are so many other religions. After all, are not all these other believers in other religions rational in believing what they believe? How could Plantinga respond to such a charge? Christians believe that people are born with original sin and that sin has damaged every facet of the person. One facet would be the cognitive faculties. God restores these faculties by the work of the Holy Spirit. Thus, non-Christians are not warranted because their cognitive mechanism is not functioning properly and is not aimed at truth. This is not necessarily their fault; the fact of sin is outside of their control. Sin also affects our affections and desires. Plantinga says that “the condition of sin involves damage to the sensus divinitatis, but not obliteration; it remains partially functional in most of us. We therefore typically have some grasp of God’s presence and properties and demands, but this knowledge is covered over, impeded, suppressed” (WCB 166-75). This could be one way to explain why there are so many religious convictions without retreating into pluralism. Isn’t The Real also a religious conviction? Does Hick consider his own view false? If he considers it true, would not he be an exclusivist? He considers every religious view other than his own to be false. There seems to be a self-defeating element to this view. The defender of proper functionalism would also charge Hick as misunderstanding the objectivity of Christian belief. He relies on internalist principles for religious experience that could be construed as subjective experience (Stairs 259). But, Plantinga’s epistemology is not subjective. The rationality of Christianity is not independent of the truth of Christianity. The pluralist misunderstands this and views all religion as a matter of interpretation.

I have sketched out Plantinga’s Reformed epistemology and the Aquinas-Calvin model. I have shown that given the noetic effects of sin that religious pluralism does not defeat Christian exclusivism. The empirical fact of sin should not cause pride but rather cause one to realize that it is because of God’s grace that one believes. Exclusivism should not be seen as prideful from a Christian worldview.

Works Cited

Plantinga, Alvin. Warrant and Proper Function. N.p.: Oxford UP, 1993. Print.

Plantinga, Alvin. Warrant: The Current Debate. New York: Oxford UP, 1993. Print.

Plantinga, Alvin. Warranted Christian Belief. New York: Oxford UP, 2000. Print.

Stairs, Allen, and Christopher Bernard. “Religious Diversity.” A Thinker’s Guide to the Philosophy of Religion. New York: Pearson Longman, 2007. 251-70. Print.